It is not very common for cultural manifestations that its origin were confined above all to one city, but sometimes it happens. In the world of music there are four well-known cases: the Tango from Buenos Aires, the Fado from Lisbon, the Rebetiko from Athens or the Rumba from Barcelona. In gastronomy this is perhaps even less frequent, but there are also cases: the Bouillabaisse from Marseille, the Salmorejo from Córdoba or… The Romesco from Tarragona, today converted into one of the stews with the most personality on the Costa Dorada.

The origins of this stew are not exactly known, although, given its culinary characteristics, it probably dates back to times before the existence of the Serrallo itself, a fishing neighborhood in Tarragona that is identified as its cradle.

Until the founding of The Serrallo neighborhood in 1860, the fishing community of the city of Tarragona lived in the old town (Part Alta). Still today, various toponyms in this area evoke the old stage of the fishermen. In an article by Jordi Bertrán it is mentioned that in the Diari de Tarragona of June 25, 1867, the toponym Serrallo was used for the first time to refer to that group of houses or huts that the fishermen have formed on the beach touching the surf of the waves, on the outside of the Francolí door.

It is not unreasonable to venture that Romesco was cooked at that time, and that its configuration of ingredients and methods could perhaps be influenced by the contact that fishermen and farmers maintained in the Part Alta, which would explain the good repertoire of Romescos of meats and vegetables that existed, although now they are less popular than fish Romescos[1]. [Precisely, in the foreword of our recent book dedicated to Romesco, Maria Mercè Martorell makes an interesting approach developing this idea (in spanish)].

Despite the fact that Romesco is probably quite an old dish, it is possible to question the theses of some passionate romescaires[2] that speak of a dish of Roman origin, because the ancho dried pepper -basic and fundamental ingredient of the Romesco- was not known until after the discovery of America. Among the oldest references that until now could be considered about the Romesco, are those that appear in two local newspapers from the 19th century:

In its edition of May 14, 1876, La Opinion, in its section dedicated to the local and provincial chronicle, makes mention of the dramatic and choreographic performances that were being prepared for the Tarragona summer season, within the framework of an initiative from the time called Campos de recreo. Among the announced works are some that the text attributes to local authors from Tarragona. One of them is called Un Romesco de peix bo (a Romesco of good fish), although no further references have been made to this work.

In its edition of December 23, 1883, El Orden, in a section dedicated published a short literary piece signed only with the name of Esperanza, in which it represents that the mayor of Tarragona talks with the governor:

(spanish)

―¿Ha comido usted pescado del que aquí se coge?

―Sí, y por cierto que me gusta mucho.

―¡Ah! ―continúa aquel― pero creo señor gobernador, que no habrá usted comido todavía romesco del que hacen los marinos.

―Ya me han hablado de él; pero á causa de la imprevista indisposición de un individuo de mi familia, no he pensado en mandar que me guisen un romesco (…)

Diferent catalan writers mention the Romesco in their works: Emili Vilanova in his Obres Completes (1906); Serafí Pitarra in Lo Cantador (1864); or Joan Pons in La colla del carrer (1887).

In any case, the first detailed reference to Romesco that is usually mentioned is a review that Ángel Muro -a prestigious gastronomer and writer of the moment- published in the newspaper La Vanguardia on May 4, 1892. The day before Ángel Muro had visited Tarragona for invitation from Joan Ruiz i Porta, who formulated it personally and publicly through a poetic letter in the Tarragona newspaper El Ferrocarril, in its edition of April 28, 1892.

His hosts from Tarragona offered Muro a local cuisine banquet with the Romesco as its central dish. Muro’s review speaks wonders of the dish, using that delicious lyrical style so typical of journalism of the time:

Anticipando artículo que escribiré debo ante todo expresar mi gratitud á la prensa tarraconense por su cariñoso saludo á mi llegada á esta capital. Motivó mi viaje, la invitación que desde las columnas de El Ferrocarril me hizo su Director señor Ruiz y Porta en brillante artículo, para probar el famoso plato, propio y exclusivo de la ciudad de Tarragona, denominado Romesco.

Llegué ayer. Causó extrañeza agradable, mi modo práctico de aceptar sin previo aviso ni cumplidos, y esta tarde á las dos en la azotea de una casa de pescadores, del barrio del Serrallo, veinte amigos presididos por el Alcalde de Tarragona, me honraban ofreciéndome una comida típica de la marinería catalana á la usanza de esta capital. Vino del Priorato en porrón, fabas á la brutesca y Lo Romesco, han compuesto la minuta. Ha oficiado de cocinero un marinero que ha dado la vuelta al mundo, para pasarse la mañana de hoy dando vueltas á los trozos de pescado base del plato, único exclusivo de Tarragona, con un sabor romano y una contextura ciclópea, que bien pudieran resucitar a un muerto. Manjar suculento. Superior á la bouillebaisse de Marsella, al rape de la coleta de Málaga á la sopa rap de los demás pueblos de la costa catalana, al arroz avanda de Valencia y todos los caldos de pescado habidos y por haber, con inclusión del primitivo manjar de los fenicios, origen de los citados y padre putativo del protagonista. Las fabas, bocado exquisito. Haciendo gala por el condimento del ázoe y del fósforo que contiene tan preciable legumbre.

En fin, comida natura, modelo de comidas, que será objeto de estudio en Conferencias Culinarias. El autor del artículo Lo Romesco, Ruiz Porta, puede estar satisfecho del éxito del banquete. Dios se lo pague.—Ángel Muro.

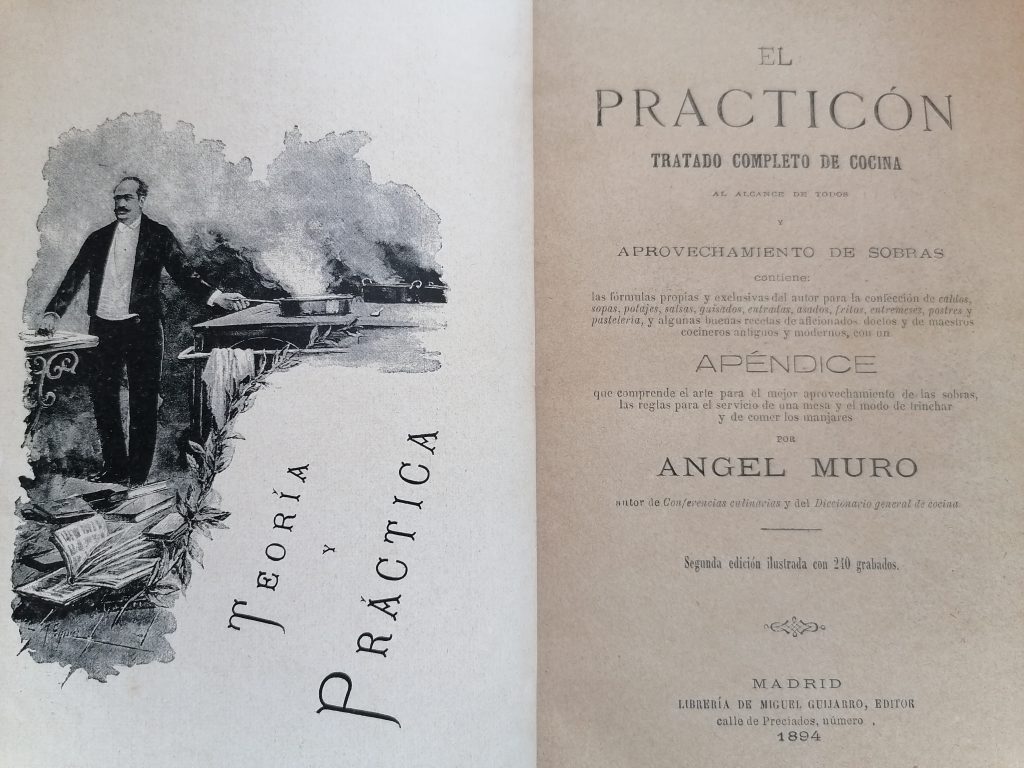

And surely Muro taken good note, since two years later (1894) he published a great cookbook with dishes from all over the Spanish geography at the end of the 19th century: El Practicón, a thick and successful text that was profusely republished in later years and that it can still be easily found in bookstores in one of its various reissues. In this book, precisely, the first known Romesco recipe was published:

(spanish)

Lo romesco

Es un plato, lo romesco, que según los hijos de Tarragona, se hace en todas partes, pero en ninguna como en su ciudad, y aún en ella, hay sitios preferidos por los muy aficionados.

Lo que quiere decir romesco nadie lo sabe, pero según lo que he podido averiguar, es el nombre típico, que habrá quedado por el uso y corruptela para denominar a la salsa, que comúnmente se sirve de aderezo al pescado guisado por los pescadores, y que se llama en todos los casos romesco.

En un caldero de hierro se fríe muy bien la menor cantidad posible de aceite, y cuando está hirviente se echan unas cabezas de ajos y una guindilla vacía por dentro, que se retira o se deja a gusto del consumidor. Después se echa muy picada otra u otras guindillas secas como la anterior, y fuera del fuego, para que no se queme ni se ennegrezca por consunción la menor película de la legumbre bermeja. Se rocía la mezcla así preparada con vino tinto del fortachón, del Priorato, y limpio de antemano el pescado de todas clases azul y blanco, grande y chico, cortado en trozos iguales, se incorpora y se agrega agua para que baje un poco durante la cocción a fuego vivo de veinte minutos.

Se sirve en cuencos de barro y resulta más sabroso cuanto más cerca del mar se come, y más fácil de digerir cuando después de haberlo comido, tiene uno que trabajar como dos, durante seis horas. Porque lo romesco, con su caldo grasiento y picante, pide mucho pan y mucho vino, y el pescado que en él se contiene es de gran fuerza alimenticia por su rápido condimento, que le hace conservar todos los principios azoados.

Me atrevería a apostar un par de pesetas a que los Celtas comían lo romesco en Tarragona, y que de ellos viene la receta que es incontestablemente de origen fenicio. ¿Qué duda tiene que los primeros pobladores de España tenían que alimentarse con pescado, y que habían de condimentarlo con aceite?

Lo del pimiento —guindilla— es una variante, pero el fondo es el mismo. Manjar fenicio, manjar matriz de la bouillebaisse de Marsella, de la Cette y de la de Tolón, del arroz-avanda de Valencia, del rap de la cocina catalana, del rape de Málaga y del Romesco. El romesco es el alimento del pescador, en tierra y embarcado.

Mientras se tienden las redes o se corren las bordadas largando y cobrando escota, uno de la lancha oficia de cocinero y fabrica del guiso, que hace desaparecer como por encanto las hogazas de pan y vaciar los porrones.

Although obviously this recipe is a deeply poetic text that already points out important and very certain aspects, such as that Romesco is tastier the closer to the sea it is eaten, the truth is that it is not a very pragmatic recipe nor does it give too much detail to who wants to try to make a Romesco. In any case, this recipe shows that Romesco at the end of the 19th century was a strong, simple, forceful, spicy stew for people of the sea, surely not within the reach of the capacity of all palates. In fact, the historical analysis of Romesco recipes shows that a progressive process of smoothing the recipe has surely taken place, with aspects such as limiting the amount of spicy or spicy ingredients, the type of fish used or the addition of nuts or tomato to the minced base[3].

In any case, both the review in La Vanguardia (1892) and the recipe in El Practicón (1894) leave little doubt about the Romesco origin of Tarragona, even mentioning its wide expansion.

Another recipe that clearly speaks of the Tarragona origin of Romesco is the one due to Ferran Agulló in his 1933 book LLibre de la Cuina Catalana (Book of Catalan Cuisine):

Peix amb «romesco» (original text in catalan).

Per terres tarragonines es conreen uns pebrots especials que en diuen «romescos» o «de romesco». Són els que donen nom a aquest cèlebre plat tarragoní, que es fa de diverses maneres segons sigui per carn, peix o bacallà.

Veu´s aquí la fórmula per al peix, que pot ésser nero, déntol, orada, gallina o polla de mar, escòrpora o rufí, garneu, lluç de palangre i fins sardina.

Es sofregeix el peix a la cassola i s´hi tira per cada 400 grams, una picada de tres grans d´all, un ramet de julivert i 100 grams d´ametlles i avellanes torrades; es deixa coure una mica.

Apart, es piquen, ben picats, després d´escaldar-los, tres o quatre pebrots de «romesco», s´hi afegeixen i es deixa acabar de coure.

La picada s´amara amb un parell de xicres d´aigua calenta.

(Spanish translation)

Pescado con «romesco»

Por tierras de Tarragona se cultivan unos pimientos especiales que llaman «romescos» o «de romesco». Son los que dan nombre a este célebre plato tarraconense, que se hace de diversas maneras según sea para carne, pescado o bacalao.

He aquí la fórmula para el pescado, que puede ser mero, dentón, dorada, gallina o polla de mar, cabracho, garneo, merluza de pincho y hasta sardina.

Se sofríe el pescado en la cazuela y se echa por cada 400 gramos, una picada de tres dientes de ajo, una rama de perejil y 100 gramos de almendras y avellanas tostadas; se deja cocer un poco.

Aparte, se pican, bien picados, después de escaldarlos tres o cuatro pimientos de «romesco», se añaden y se deja terminar de cocer.

La picada se remoja con un par de tazas de agua caliente.

It is notable that in Agulló’s recipe almonds and hazelnuts are mentioned, which was not the case in Muro’s recipe. This issue of the addition of nuts to the Romesco base mince must have generated some debate at the time and even its current implementation. Artur Roca -contestant who obtained the title of Mestre Romescaire (Master of Romesco) in the I Concurso de «Mestres Romescaires» (I contest of Masters of Romesco) that was held in the Serrallo on June 3, 1951- did not consider using nuts in the Romesco, according to an interview they did in Diario Español on May 27, 1960. However, Carme Brull, the winner of this very first edition of the contest, explained in detail in an interview in that same media (June 10, 1951) his champion recipe, which contained fifty grams of almonds, as will be described later.

1951 was precisely a great year for Romesco. Thanks to the enthusiasm of diferent intellectuals from Tarragona such as Antoni Alasà, better known by the nickname of Máximo Burxa, or also the collective of the Tarragona Sindicat d´Iniciativa i Turisme -SIT- (a historical local cultural association), on June 3 celebrates in the Serrallo de Tarragona, with great display of media and expectation, the I Concurso de «Mestres Romescaires» (I contest of Masters of the Romesco), under the auspices of the aforementioned SIT and other promoters; a contest that would already be scheduled with different periodicity and in various places in The Serrallo since then.

In this contest, the participants measured their skills by preparing the same Romesco in a traditional oak charcoal stove, like the ones that used to equip fishermen’s boats. This Romesco was normally of monkfish, although there were years when the base fish was changed, as happened in 1953, the year in which corvina was used. In this contest, the highest ranked participants obtained the brand new title of Mestre Romescaire (Master of the Romesco) or, in the case of the champions of each edition, that of Mestre Major Romescaire (Great Master of the Romesco). After many editions since 1951, there are already diverse Romesco lovers who are in proud possession of these degrees[4].

The press coverage of the first romescaires contest allows us to have the recipe that the winner of the contest —Carme Brull— used, since she explained it in good detail in an interview in Diario Español on June 10, 1951 (this recipe was probably for six people):

Two “romesco pebrots” (ancho dried peppers) are fried together with a slice of bread, five or six garlic and fifty grams of almonds. Once fried, put everything together in the mortar and make mincemeat. It is mixed with water and everything is added to the casserole and then the fish is added, which can also be «rap», «llobarro», «lluerna» or «rata».

It should be noted that, in this same interview, Carme Brull mentions that she usually used to serve her Romesco with aioli, although on this occasion she had not done so in order to comply with the rules of the contest.

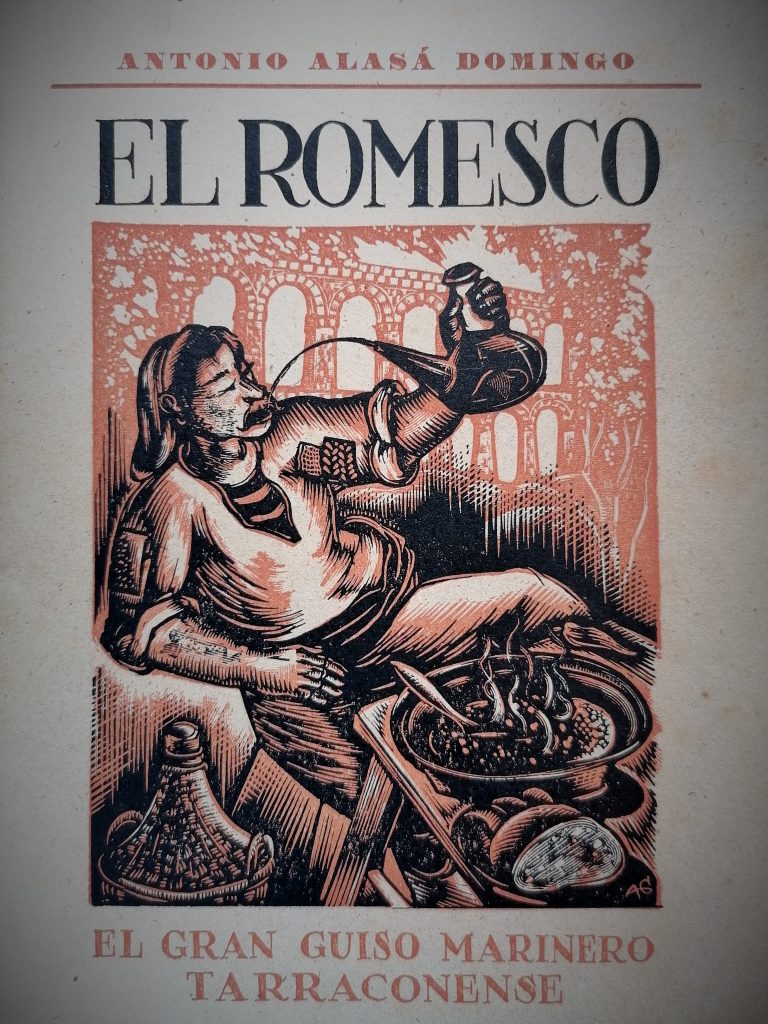

That same year of 1951, Máximo Burxa published a beautiful and poetic little book on Romesco edited by the SIT itself that would become a reference at the local level, accumulating no less than four editions in total with hardly any changes (1951, 1974, 1993 and 2019, the last two in catalan) and which contains an extraordinary prologue by Josep Pla, in which the author highlights the very, particular and unique thing that the Romesco is from Tarragona.

The SIT would schedule the «Mestres Romescaires» Contest from 1951 to its XXVII edition, held during the Sta. Tecla major festivities in 2014. It would not be until 2019 that the contest would be recovered again, at which time the SIT gave up the organization’s baton of the contest to a group of diverse local organizations.

The 60s started very well for the small world of Romesco. That same year, 1960, the so-called Olimpíada Romescaire took place, an important popular act in favor of the Romesco, whose final moment on September 22, 1960 in the Serrallo of Tarragona, was called Gran Sarao de los mil romescos and a thousand servings of Romesco were served there. This Gran Sarao dedicated his benefits to the asylum of the Hermanitas de los pobres, in order to help build a pavilion dedicated to elderly couples.

On the other hand, and thanks to the support of a local bank, in 1962 Antoni Alasà -Máximo Burxa- launched a new book that would become a benchmark for Tarragona’s local cuisine: La cocina de mi tierra. With his unmistakable and delicate style de él, Burxa describes in his book, among others, two Romesco recipes: one for the traditional fish Romesco and the other for a meat-based Romesco (the Romesco of bull with snails). The latter is an elaboration that has practically disappeared today, but was once a traditional one of the months with bullfighting in Tarragona.

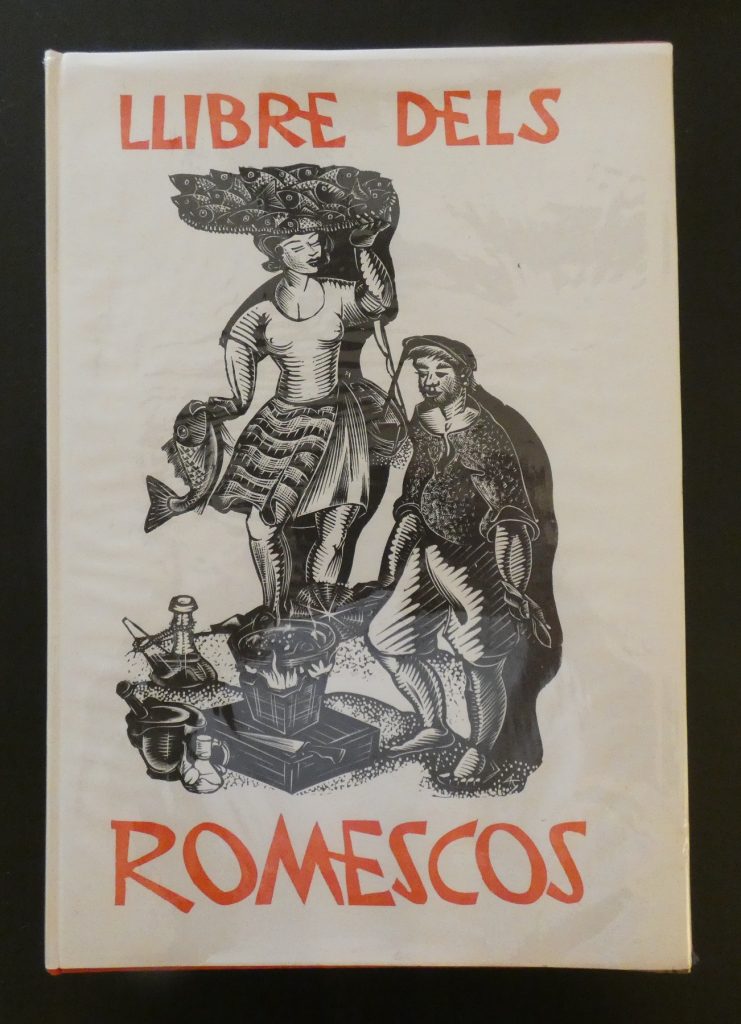

In 1963 a very delicate book appeared in Catalan by Antoni Gelabert. El llibre dels romescos (The book of the Romescos). This book is an excellent edition, with a cultured and rigorous text and contains some precious woodcuts by Gelabert himself, which have become the basis of the popular graphic image of the Romesco. This is truly a book for bibliophiles that is completely delightful in every way. From this volume it is worth highlighting a short and beautiful fragment, which could well be used as an introductory reading before each Romesco meal:

(original text in catalan)

I sempre, en el fons, Tarragona!. Perquè si quan teniu enfront vostre, intacta encara, la platera fumejant i curulla, no sou capaços d’evocar el tumult de records, sentiments i rostres, paraules i cançons, els cels i els marges ordenats, les oliveres i les vinyes, la lluïsor de l’escata, l’alateig del peix, l’ardència del sol, l’olor penetrant del roquer, l’ombra fugissera del llobarro en el trencall de les onades… si no sou capaços d’evocar tot això i tantes altres coses, no gustareu mai el sabor inefable del Romesco!

Antoni Gelabert en «El Llibre dels Romescos», 1963.

(Spanish translation)

¡Y siempre, de fondo, Tarragona!. Porque si cuando tenéis frente a vosotros, intacta aún, la cazuela humeante y rebosante, no sois capaces de evocar el tumulto de recuerdos, sentimientos y rostros, palabras y canciones, los cielos y los ribazos ordenados, los olivos y las viñas, la brillantez de la escama, el aleteo del pescado, el ardor del sol, el olor penetrante del roquero, la sombra huidiza de la lubina en el romper de las olas… Si no sois capaces de evocar todo esto y tantas otras cosas ¡no disfrutaréis jamás del sabor inefable del Romesco!

Antoni Gelabert en «El Llibre dels Romescos», 1963.

(english)

And always, in the background, Tarragona! Because if when you have in front of you, still intact, the steaming and overflowing casserole, you are not able to evoke the tumult of memories, feelings and faces, words and songs, the heavens and the ordered banks, the olive trees and the vineyards, the brilliance of the scale, the flapping of the fish, the burning of the sun, the penetrating smell of the rocker, the fleeting shadow of the sea bass in the breaking of the waves … If you are not able to evoke all this and so many other things, you will not enjoy never the ineffable flavor of Romesco!

Antoni Gelabert en «El Llibre dels Romescos», 1963.

It is striking that in the woodcut on the cover of Gelabert’s book there is an earthenware stove with a casserole in which a Romesco is cooked, very similar to the pieces that can be seen in the Museum of the Port of Tarragona, dated in the first middle of the 20th century, and which are donations of A. Pedrol and C. Pedrol.

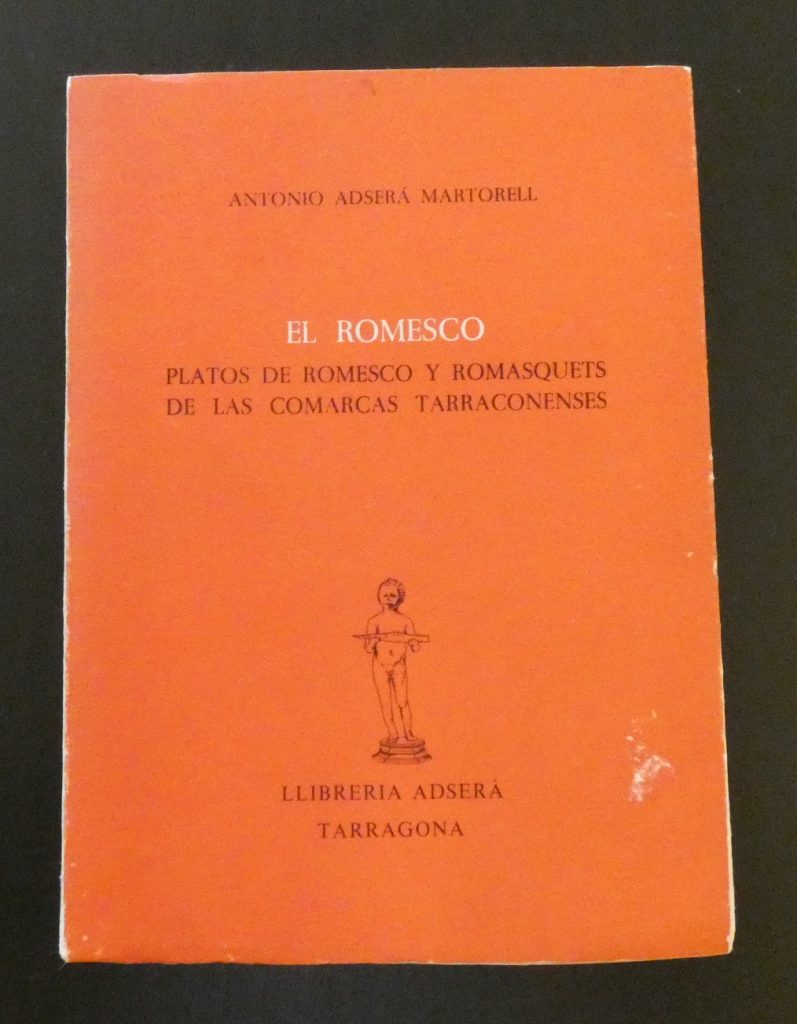

Already in 1981 the prestigious local bookseller and intellectual Antoni Adserà made a necessary contribution to the world of Romesco with his book El Romesco. Platos de romesco y romasquets de la comarca de Tarragona, which in 1997 would be revised and reissued in catalan. His book is a treatise on Romesco that not only offers detailed recipes, but also speaks of Romesco from a social and historical perspective. It is at least curious that three great supporters of Romesco during the 20th century were called by the same Christian name (Antoni Alasà -Máximo Burxa-, Antoni Gelabert and Antoni Adserà). And it should be said that David Solé, already in this century, is called Antoni by his middle name.

On June 20, 1982 a great romescaire event takes place in the Serrallo. Fifteen hundred romescos were cooked and tasted in the fishermen’s district with great success. The event was led by the famous local journalist Josep Maria Tarrasa. Groups of castellers performed and the famous gastronomic chronicler Luis Bettonica gave a lecture on the Romesco. A posthumous tribute was paid to Antoni Alasà -Máximo Burxa-, who had died the previous year. For this reason, a commemorative plaque was given to León, one of Burxa’s sons.

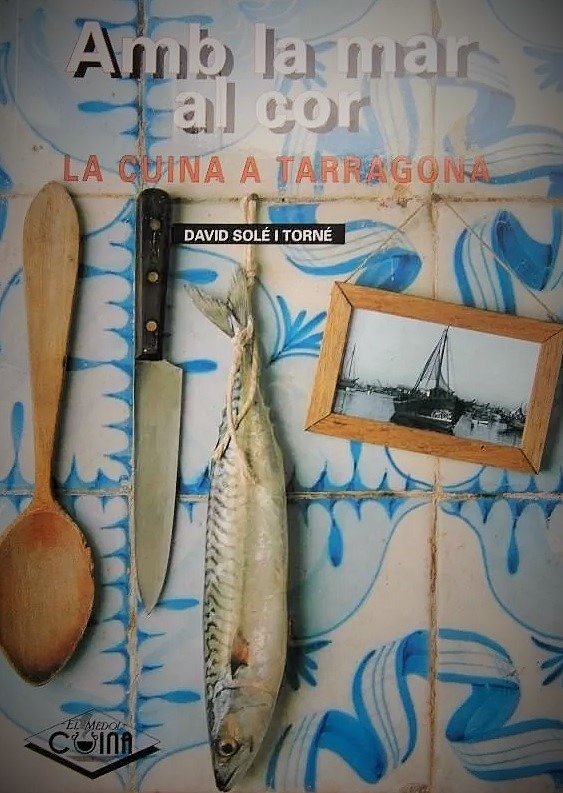

Starting in the nineties, various books with Romesco recipes appeared, written with great practical and informative sense, although at the same time documented and rigorous in traditional uses and customs. In this sense, the local chef David Solé can be mentioned Amb la mar al cor (1993, catalan), Peix, cuina i tradició (1997, catalan) or El Romesco (2003, catalan). From the author Carme Arjona, we can cite La cuina del Serrallo (1999, catalan).

In this effort to print an informative tone to the kitchen, it is worth highlighting the aforementioned book Amb la mar al cor (David Solé, 1993). This volume offers a series of very affordable local seafood recipes, at a time when there were not so many Internet or bibliographic resources. This particular text is therefore especially relevant, since in its section dedicated to the Romesco, a series of ten Romesco recipes are published totally within the reach of any fan.

There do not seem to be differences between the three most common names for Romesco: Romesco, Romescada and Romesquet, apart from the fact that the term Romesco is the most used in the existing bibliography. Some suggest that it could be an aspect that had to do with the size of the stew. Thus, Romesco would be applied to a stew for between four and ten people, while Romescada would be a proper denomination of casseroles for more diners. Lastly, Romesquet would apply to stews of fewer than four people.

Nowadays, the world of Romesco is not exactly going through a great moment of popularity, although new impulses can be expected. Despite various recent initiatives around Romesco with more or less fortunate results, it may not be possible to speak today of the same enthusiasm that inspired the great events dedicated to Romesco in the mid-twentieth century. Unlike other autochthonous dishes of its geographies, Romesco is a stew that deserves to be better known outside its place of origin; in fact, it must be admitted that the Romesco could be better promoted and known in Tarragona itself. The contemporary lifestyle seems to be that it is not there to spend time in the kitchen, although those are things that can change, and it is possible that in the world of Romesco the best is yet to come.

[1] L´origen del nom «Colla de la Mercè», by Jordi Bertrán. Fet a Tarragona, 2015 (catalan).

[2] This is how Romesco’s cooks are called in catalan.

[3] In this process, the culinary contribution of the housewives should have been relevant, in addition to the elaborations of the boat cooks.

[4] It should be noted that in other towns in the province there are also contests and contests dedicated to Romesco.